Many of us in Sabah are familiar with the ruins of what was

once the magnificent Kinarut

Mansion

|

| Kinarut Mansion ruins (Photo credit: Richard Sokial) |

Asimont was an expert on rubber and was hired as the first

manager of the Kinarut Estate, a rubber plantation owned by a British company

called Manchester North Borneo Ltd. It was the second largest rubber estate

after Sapong Estate. Asimont was interned during WWI and, apparently, that was

the last thing people knew about him. There had been other Germans in NB and

they came long before Asimont. Somehow, like Asimont, their stint in NB had

been short and—shall we say, disastrous?

Twenty-six years before Mr. Asimont’s sojourn at Kinarut

Estate, two Germans—Herman Friedrich Meyerink and Friedrich Hockmeyer—founded

the German Borneo Company (GBC) in Germany

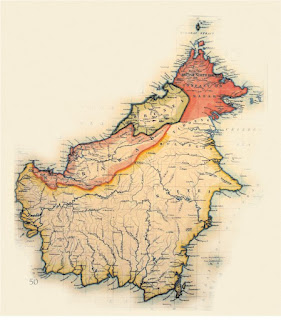

|

| Map of northern Sabah (North Borneo) |

H.F. Meyerink and his assistant, Carl Eduard Funcke, arrived

in Banguey in 1884 where they established Hacienda Nicolina. Chinese coolies

were employed to work on the plantation. However, by mid-year a group of

coolies revolted, stole a boat and attempted to escape. Meyerink and his

assistant pursued the fleeing coolies and when they were threatened with

parangs, the Germans fired several shots. Two men later succumbed to their

injuries. The NBCC was blamed for the deaths through its failure to take the

wounded to the Kudat

Hospital

Naturally, the NBCC wasn’t too pleased! The company started an

investigation which revealed that the coolies were forced to endure bad working

and living conditions, ill-treatment by the German managers and Meyerink’s

ill-temper. Now it was the Germans’ turn to get upset because they faced ten

years in prison! They had come to Borneo to

make money for the GBC, not to rot in some prison!

They solved their problem by leaving Hacienda Nicolina in the

hands of one John Carnarvon before fleeing to Jolo in August 1884. They established

a new plantation on Jolo, Gomantong Plantation, on behalf of the GBC. We have

to give them credit for their diligence, for not wasting any time moaning about

their misfortune and for being responsible to the shareholders of GBC.

However, fortune wasn’t on their side. It was more like

out-of-the-frying-pan-into-the-fire kind of situation. The Gomantong Plantation

in Jolo was doomed from the start. A civil war raged—the result of conflicts of

succession caused by the death of the sultan. There were numerous attacks on

the plantation: the coolies died or were injured; the Germans were threatened;

cultivation and harvesting were hampered.

When the Spaniards failed to curb the attacks, Meyerink sent

an SOS to Germany Spain

suspected Germany

Meanwhile, back at Hacienda Nicolina in Banguey with John

Carnarvon, the situation wasn’t much better. Hamburg Somalia

|

| What the Kinarut Mansion looked like before it was demolished (Drawn by Richard Sokial) |

In January 1889, exactly five years after the GBC was

founded, the board of directors decided to dissolve the company, thus ending

the presence of a German company in NB.

Can you imagine what could have happened if the GBC’s

ventures had been successful in Banggi and Bengkoka? (During that time Germany had colonized part of New Guinea Kinarut Mansion

could still be standing and looking out into the South

China Sea !

|

| A beautiful book to treasure! |

Reference: The Sarawak Museum

Journal; Colonial Townships in Sabah